The Shortcut Blog

Articles and Thoughts on Engineering, Product, Design, Best Practices, and more.

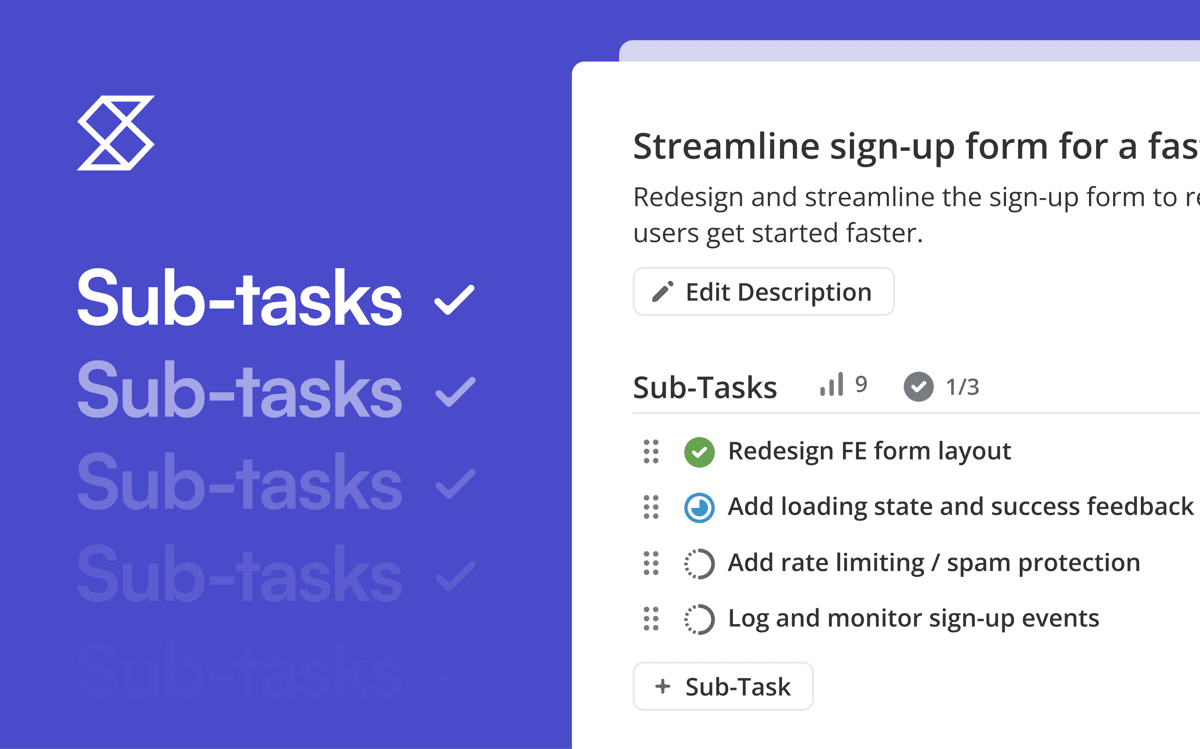

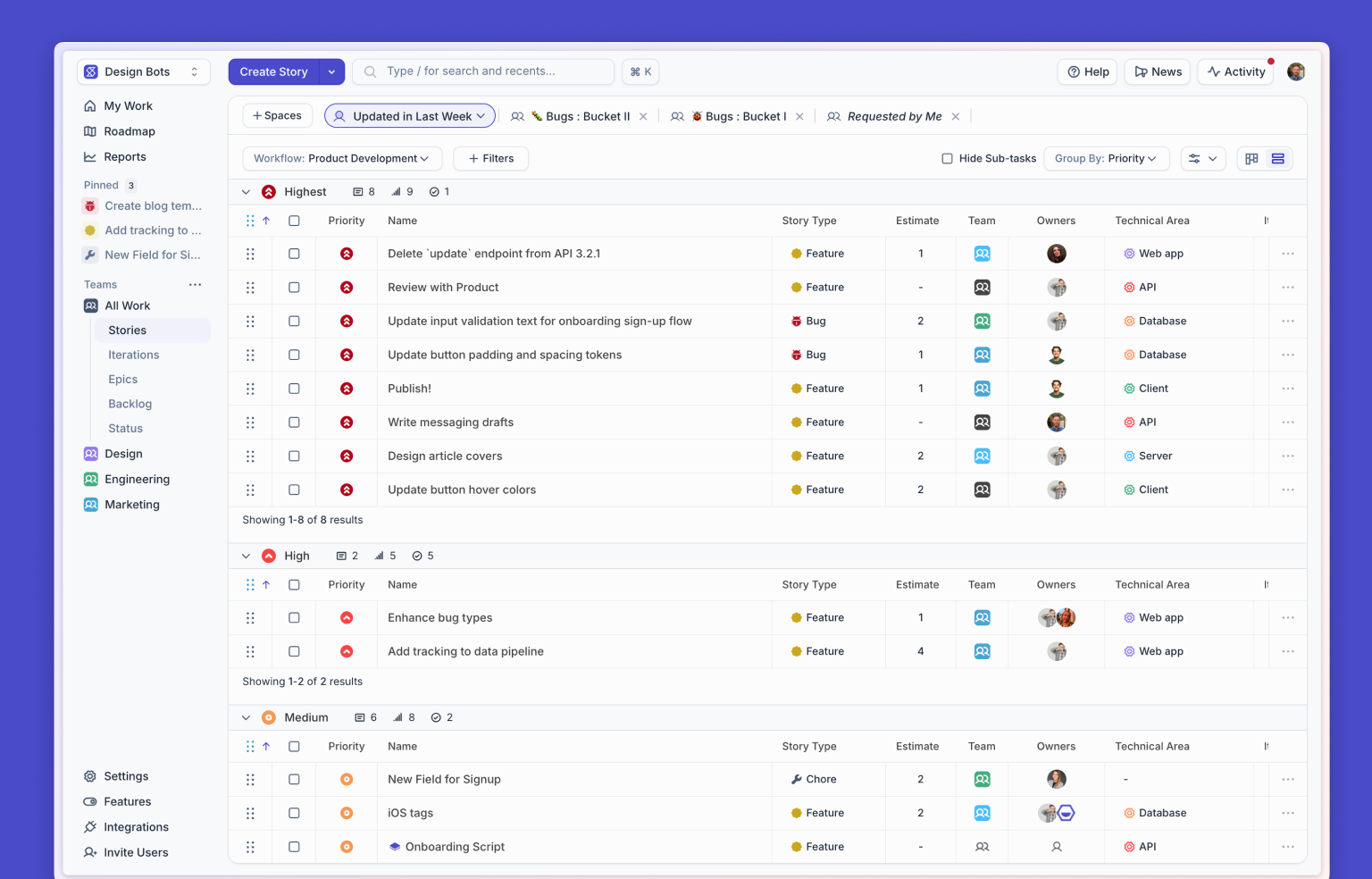

Today, we’re introducing the new Shortcut look: a calmer, clearer, faster, and more focused experience built to help teams stay focused on what matters.This redesign isn’t just about looks. It’s about making Shortcut simpler in everything you do; from planning your next sprint to getting your next story done.

To Build the Future: Ada Lovelace and the Unseen Worlds of Engineering

%20(788%20x%20492%20px)%20(1).png)

.png)